There was a time where poetry and punk rock were pretty much the most important things in my life. Right up there with partying! I may never have owned a leather jacket or developed a penchant for turtleneck sweaters. But during those years, I was completely obsessed, if not very adept; enthusiastic if not particularly well-suited for the discipline both practices require for sustained success.

I fell hard for both around the same time, as my teenage years gave way to my early twenties. By way of mail-order catalogues, I’d gotten into the DIY punk scene from afar while in high school. Meanwhile, my budding interest in poetry was encouraged early on by Donna Kane, a local Peace Region poet, and Jaime Denike, a classmate of mine from Capilano College in North Vancouver. From there, I stubbornly struck out on my own.

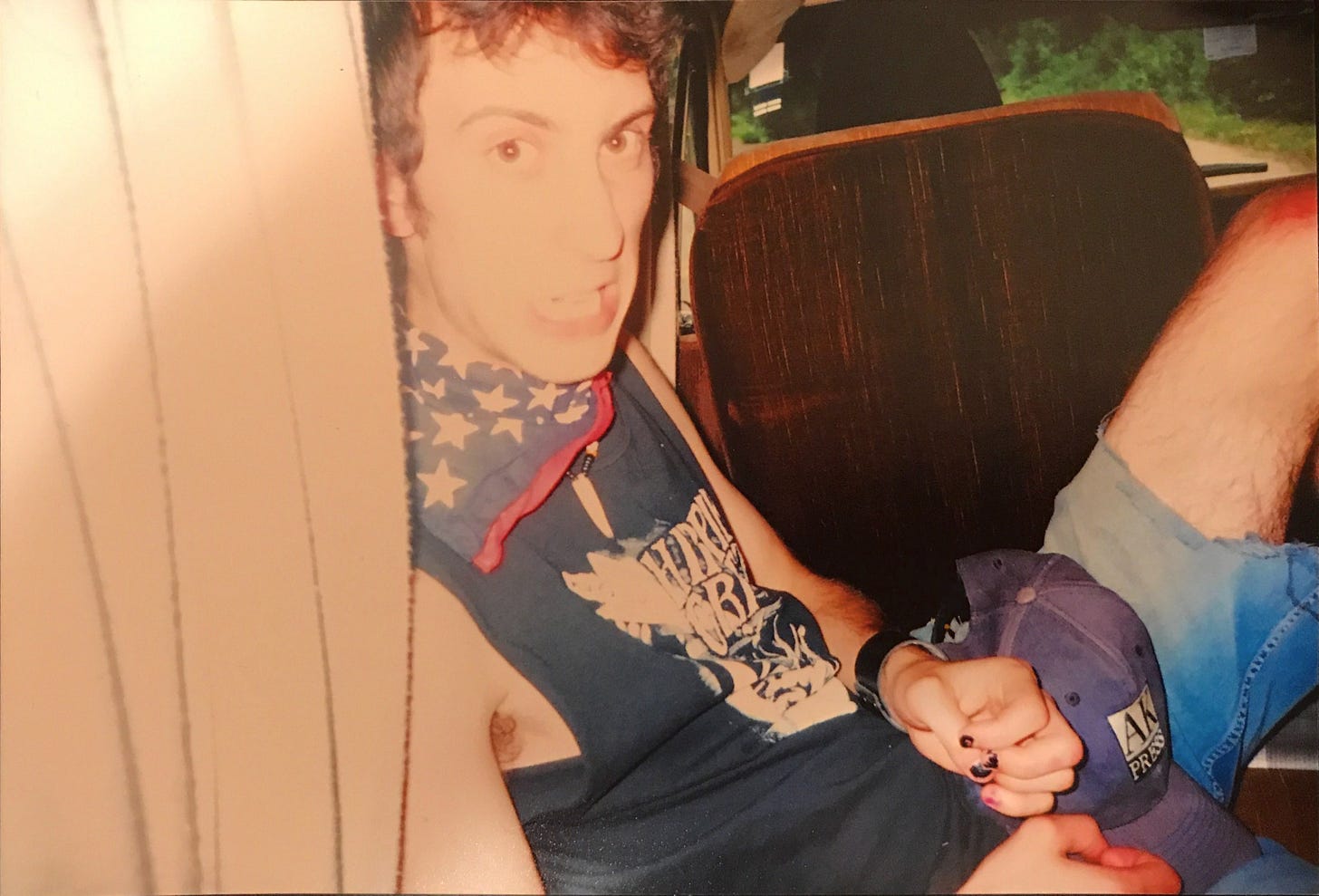

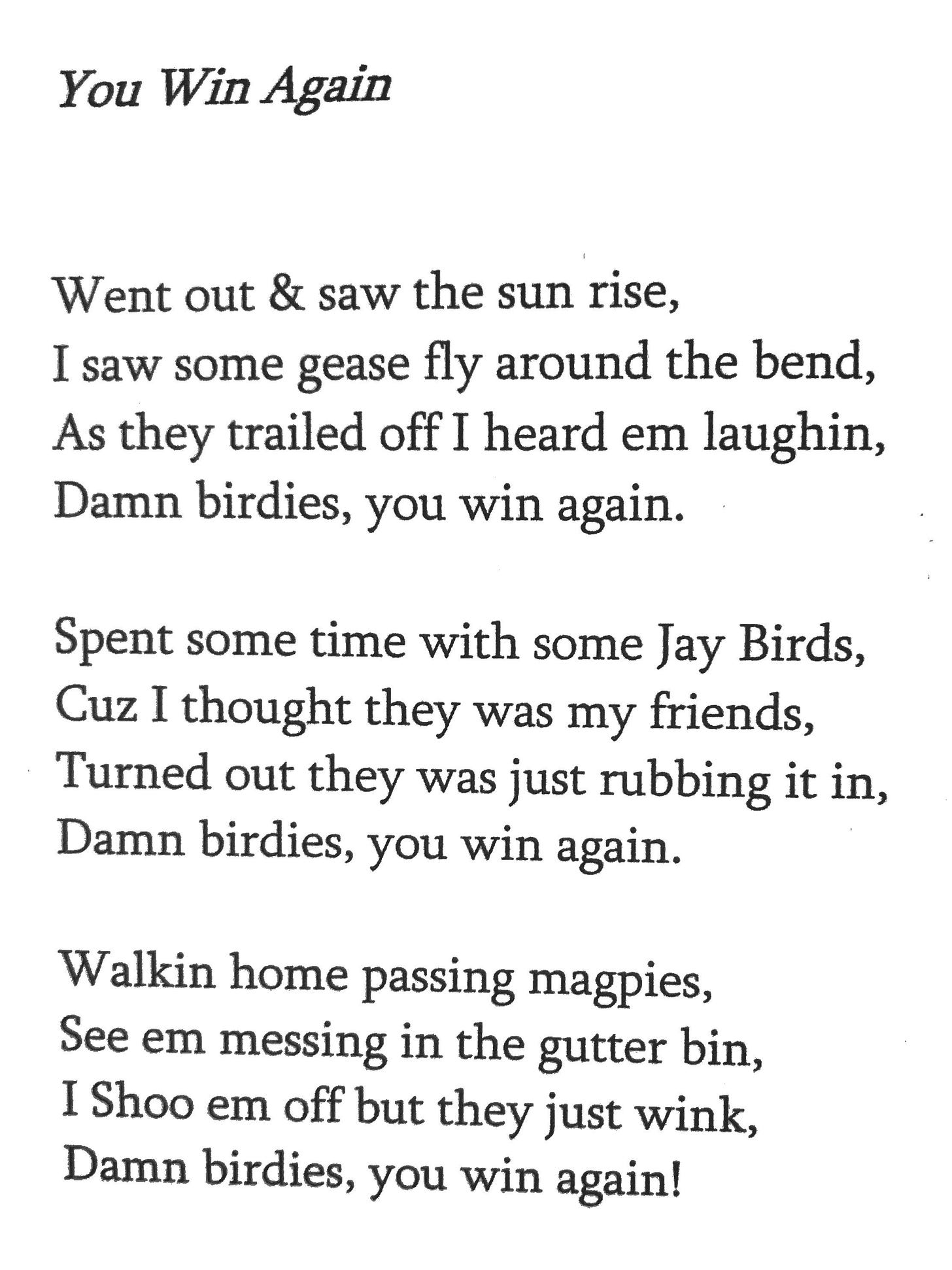

(published in The Liar, Capilano College student literary journal 2002/2003)

From the printed page, I took quickly (for good or ill) to the poetry of Bukowski and Al Purdy; Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter, George Elliot Clarke’s Whylah Falls, and Michael Turner’s Hard Core Logo featured writing about music (and race, in the former cases) that was unlike anything I had ever read before; Kroetsch’s Seed Catalogue was a revelation when first it crossed my path. And while Please Kill Me was like a punk rock Bible to me I many ways during those early years, my own early inspirations, poetically, came by way of the lyrics of Nick Cave, John K Samson and Christine Fellows rather than Lou Reed, Patti Smith, or Tom Verlaine. Clive Holden’s Trains of Winnipeg project brought the DIY indie/punk rock and poetry worlds together (to say nothing of the film portion of the project) in a way that really captured my imagination. The project sets Holden’s spoken word poetry set to music by Samson, Fellows, and Weakerthans/Red Fisher drummer Jason Tait.

When I interviewed Samson for the series of articles which formed the foundation that Missing Like Teeth was built on, he spoke at length about the importance of zines to his own development as a writer.

“They were a way a lot of us communicated, in a way. Kind of saying the things we couldn’t say or didn’t want to say,” mused John K Samson, who today runs Arbeiter Ring Publishing, a radical publishing house, in Winnipeg. “Zine culture is certainly why Todd Scarth and I started a publishing house, and is still the ethic, I think, that drives what we do almost 20 years later.”

Emboldened by the DIY ethos of punk rock, I started making zines of my own, then made the jump to chapbooks (which I still take to be the 7” of the literary world, in the best possible way). I attended both poetry readings and punk shows in weird venues, from old grain elevators and laundromats to student union buildings and basement bars; sometimes the two shared a bill. I bought a crappy guitar, started a punk band, and dropped out of college. Then we dragged our deranged act back and forth across the prairies, playing all the dives from the Cobalt to the Albert, not to mention community centres and punk houses. All the while, I was scribbling scraps of poetry into notebooks, onto napkins and coasters, before typing it up on the Dell laptop I dragged around to the rooms in North Vancouver, Kelowna, Clear Lake, and Dawson Creek that I called home during those years. The amount I paid in postage submitting poetry, not to mention the required SASE, was second only to beer and used vinyl records in those days, I’m sure.

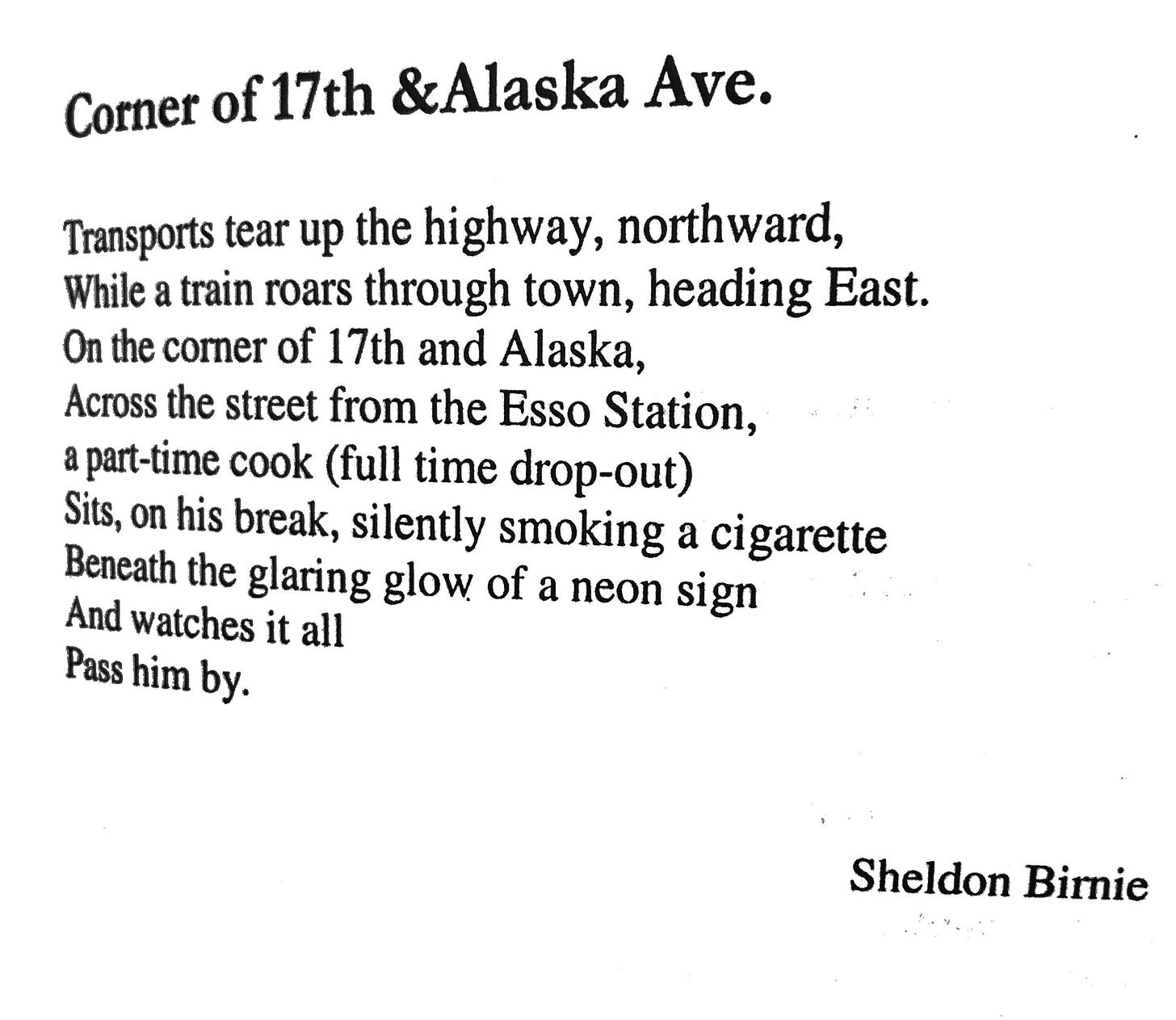

(published in Claremont Review No 24/Fall 2003)

Between 2002 and 2007, the punk band I was in played dozens of shows and got ourselves our banned from most reputable venues across British Columbia and the prairies, made some barely listenable recordings, and then fizzled out into obscurity. About that same time, give or two a year in either direction, about a dozen of my poems found homes in literary journals, more still in scattered zines and eventually online. I published a chapbook a year in those days, traded them away for drinks or drugs. I’d swing the same deal for our CDRs or t-shirts often enough too, come to think of it. The words and the music were making their way out into the world, and that was all you ask for, wasn’t it?

Not to discount the hours of work it takes to finesse a piece of art into shape, but there is something appealing in how raw and unrefined punk and poetry can be. As a highly disaffected but undeniably bookish young man, that hit a nerve with me, big time. In both forms, the performer can go all out in pursuit of expressing whatever the hell it is that’s screaming to be let out. Let it bleed. Let’s get nasty here. If need be, pour a little 151 to disinfect the wounds. Or just let ‘em fester.

(The Tups @ The Beach Club Bar, Wasagaming, Manitoba Aug. 9, 2004)

The fleeting nature of art lends itself well to both punk and poetry. The artist burns brightly against the darkness, but in the end the darkness remains, indomitable dark. The old burn.flicker.die. It’s like Bukowski said; the poet, in the end, is but

born to hustle roses down the avenues of the dead

Now, not every word I wrote those days made its way into a poem. I’m willing to admit that I fucked around with fiction all the while, and even got my first byline as a rogue correspondent and concert reviewer in an alt-monthly out of Vancouver that went belly up shortly thereafter. I even started writing my own songs, albeit in the alt-country vein (my primary lyrical contribution to The Tups being a little ditty called “Sweatpants Boner”). But for the most part, it was poetry and punk rock all the way for me for a while there. Until it wasn’t anymore.

Around the time I started going to university (for real, this time), I got involved with the student paper, and the rest as they say is history. Like countless other would-be writers before me, the ability to eke out a living in the field of journalism was too good a opportunity to pass up, even if the pay is poor and the opportunities to do so are scanter by the day. And, like many punk rockers from John Doe onwards, when my punk band died, an alt-country band rose from its ashes. It’s been a while since we played a show, nowadays, but for over a decade we plugged away at hundreds of gigs, and put out a few half-listenable records to boot.

Poetry, like punk rock, takes passion and dedication if it is to be practised with any sincerity. And of course, if either poetry or punk rock are lacking whatsoever in sincerity, what good is the end product anyway? Posers are celebrated by neither poets nor punks, or so both camps would have you believe.

Now, nearly 20 years on, I can’t say that I actively do much by way of either art form. Sure, the last couple shows I went to before these dark corona times shut the world down were punk shows — the Descendents and Propagandhi, respectively — and the last library book I returned was a collection of Berryman’s work. But that is far from a living and breathing practice.

But the years spent in the pits and pouring over pages of poetry have left their marks, and then some. The old adage that three chords and the truth are all you need for a song holds as true to me today as it did 20 years ago. Similarly, I’d like to think the best stuff I hammer out on the keyboard is imbued with some touch of poetry, if only in passing. That may be wishful thinking on both counts. But like Mars, punk rock and poetry are both the dominion of dreamers, albeit disaffected ones. And if you can’t count yourself among the dreamers, then you better just count yourself right out.

(from chapbook of the same name, self-published, 2005)